Here are some examples of things you might come up with during the Analysis phase and examples of them. Instead of using an information literacy skills example, I am going to use the example of training new graduate student workers to work at the RIS desk. I will focus on just one aspect of this training: using the printer/scanner/copier in the workroom. In this case, I will pretend I am making a training binder with step-by-step instructions, not a video.

Learner Analysis

Without doing an in-depth analysis, I can think about what I do know about my learners. I know that my learners are graduate students, that they work approximately 12 hours a week on the desk, and that they are concerned about getting some homework done while on the desk. They often work without direct supervision on nights and weekends. Since I was part of the hiring process, I can say that 2 have experience working in an office prior to coming to the library and the others do not. I also know their majors. This information tells me that they are going to be motivated, but they may also not remember how to use the copier when it comes time to use it, and that I may not be there to show them what to do. From this analysis, I have decided to create a pamphlet with images on it so they can follow along with my instructions when I am not available to help. This is another part of the Analysis phase--determining the best course of instruction for the instructional problem.

Instructional Goal

You will want to craft an instructional goal that the instruction hopes to solve. Here is an example of an instructional goal:

As part of their office skills

training, Graduate Assistants will complete the process of collating and

stapling a copied document using the Toshiba e-Studio 356 copier in the

Research and Instructional Services Workroom.

Performance Objectives

You may want to think through what success would look like if the learners complete the goal. Here are some sample objectives related to the graduate student example:

Objective 1: Graduate Assistants should be able to define the terms

collate

and staple

in relation to copying and explain the use of collation and stapling documents without

error.

Objective 2: With the use of the training pamphlet, Graduate

Assistants should demonstrate the use of the touch panel and options on the

Toshiba copier to collate and staple a photocopied document.

Sub-objective 2a: Using the graphic on

page 3 of the training pamphlet as a guide, Graduate Assistants should be able

to identify the location of the collate option on the Toshiba touch control

panel and set the collate option to Rotate Collate.

Sub-objective 2b: Using the graphic on

page 4 of the training pamphlet as a guide, Graduate Assistants should be able

to identify the location of the staple option on the touch control panel and

set this option to staple 1 staple in the upper left of the copied document.

Project Needs and Timeline

Another thing to think through in the Analysis phase is how long it will take to create the tutorial. In this case, I can create this instruction in about 3 hours using a still image camera and Microsoft Word. I know how to do this already, so the instruction will not take long to create. In the case of a video, you may have to learn to use Camtasia or a video editing suite. You may have to get that software installed on your computer from an IT department. Think through what you will need to do before you get started.

Many times, I find myself underestimating the Analysis phase, but as you can see, if you start out with a strong analysis of your needs and your learners' needs, you will have fewer surprises later.

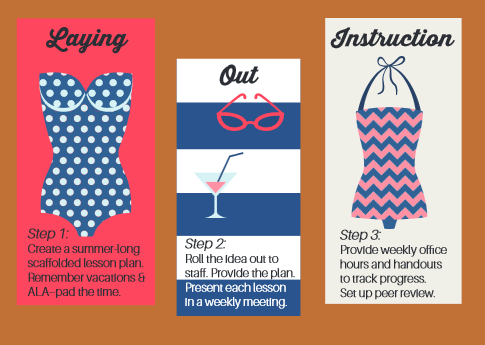

Join me next week for a breakdown of the Design phase!